Understanding the Distinction: How Recognizing the Difference Between Bullying and Mobbing Empowers HR Professionals and Organizational Leaders

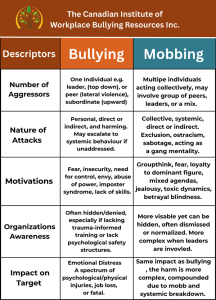

The behaviors associated with workplace bullying and mobbing are often very similar: manipulation, exclusion, belittling, undermining, or sabotaging someone’s work or reputation. The tactics overlap significantly, as does the impact on the target: emotional distress, physical symptoms, job loss, and, in severe cases, long-term psychological injury.

Where the Terms Come From

The term ‘bullying‘ has its roots in 18th-century English, originally referring to physical intimidation or coercion. Over time, it expanded to encompass emotional, psychological, and verbal abuse, particularly in educational institutions and later in the workplace. On the other hand, ‘mobbing‘ is derived from the ethnological work of Konrad Lorenz in the 1960s. He used it to describe the behavior of small animals banding together to repel a predator. Swedish researcher Heinz Leymann later applied this term to human behavior in the workplace in the 1980s, identifying it as a collective form of harassment.

Bullying usually involves a single Psychological Safety Violator (PSV) an individual who violates the emotional, psychological, or relational safety of another person through repeated and targeted harm. A PSV can be a peer, subordinate, or leader who misuses power, disregards boundaries, or creates persistent distress.

Linda Crockett, founder of the Canadian Institute of Workplace Bullying Resources, coined the term psychological safety violator (PSV). This term encompasses a wide range of workplace psychological hazards, including bullying, mobbing, lateral violence, harassment, discrimination, and racism. By using one unified term, PSV reflects the common denominator behind these actions: the violation of another person’s psychological safety. This terminology is beneficial in trauma-informed frameworks, where the emphasis is on behavior and harm rather than permanent labels.

Mobbing, conversely, involves a group—knowingly or passively—engaging in persistent harassment, often following an extroverted or introverted leader’s cues or as a form of social alignment. Mobbing tends to be more systemic and sustained, usually supported (or ignored) by institutional structures.

What distinguishes mobbing is not the nature of the harm but the number of Psychological Safety Violators and the scale of the betrayal. Mobbing occurs when two or more individuals act together, consciously or unconsciously, to isolate, devalue, and psychologically harm a colleague. These groups may consist of peers, leaders, or a combination. When leaders are involved, the situation becomes significantly more complex and damaging, especially when institutional protection is absent or complicit.

Top-Down, Bottom-Up, and Lateral Violence

Bullying and mobbing can be top-down (from leaders toward subordinates), bottom-up (from staff toward a leader), or lateral (peer-to-peer). These dynamics can involve Psychological Safety Violators who consciously or unconsciously harm others by undermining emotional security, trust, or fairness.

Lateral violence is widespread in environments where oppression, trauma, or systemic inequities are present. It reflects displaced aggression, where employees harm each other instead of confronting root causes or systemic issues. In First Nations communities, for example, lateral violence has been identified as a legacy of colonial trauma and systemic disempowerment. In corporate or academic settings, it often manifests through subtle undermining, exclusion, or the weaponization of policies.

A Real-World Example

Consider this true story, a case of a safety officer in the oil industry, a dedicated, ethical employee who loved his work. A manager, for reasons rooted in control and power, began targeting him by enlisting staff to play daily tricks and sabotage minor aspects of his workstation. These acts may seem trivial in isolation, but cumulatively, they became a steady stream of microaggressions and psychological stressors.

The breaking point came when the manager opened the officer’s desk drawer, photocopied his private journal, and distributed it to staff. The humiliation and betrayal were profound. This abuse of his privacy wasn’t just inappropriate behavior, it was psychological violence, a profound violation of trust and dignity. That manager was a clear example of a Psychological Safety Violator. The safety officer developed severe depression and had to take sick leave.

Worse still, the organization’s leadership—specifically the CEO—chose to protect the manager instead of the injured worker. This complex abuse is a prime example of institutional betrayal: when those with the responsibility and authority to protect employees instead perpetuate or shield those causing harm. It’s a double wound—one from the abuser and one from the system meant to provide safety.

Why Distinction Matters

While bullying by an individual is certainly damaging, when it escalates into mobbing, a collective campaign of harm, it not only intensifies the trauma but also undermines the foundation of psychological safety in the entire organization. When leaders either participate in or turn a blind eye to such behavior, they are sending a clear and dangerous message: abuse is tolerated here. This silence, denial, or protection of Psychological Safety Violators exacerbates the injury and contributes to long-term organizational damage.

Systemic Responses: The Urgent Need to Address Mobbing in the Workplace

Self-Awareness and Accountability: The Personal Responsibility in Addressing Workplace Issues

Whether someone has participated in bullying behavior directly or indirectly, change begins with courageous self-reflection. Individuals can ask: “Where might I have been complicit? Have I allowed gossip, exclusion, or silence to replace empathy or fairness? Have I stood by when I should have spoken up?” Developing self-confidence, self-worth, and self-respect involves being honest about one’s behaviors.

Genuine accountability means aligning actions with one’s values, morals, and ethical standards, even when uncomfortable. It also involves repairing harm where possible. Repair includes offering sincere apologies, participating in restorative practices, and committing to ongoing education about psychological safety and trauma-informed practices.

It’s not enough to say you believe in respect—you must model it, especially when tensions rise, or systems fail. As more people engage in this level of integrity, we foster a workplace culture where safety is not just policy, it’s practice.

Key Solutions and Recommendations

- Provide trauma-informed education for all staff on the difference between bullying, mobbing, lateral violence, and healthy conflict. Ensure every employee knows their rights and the psychological hazard policies that protect them.

- Require leaders to undergo trauma-informed leadership training for prevention, skilled intervention, and repair and recovery options.

- Create independent, third-party reporting mechanisms.

- Contract workplace psychological safety, trauma-informed therapists who are also consultants for these types of cases, as part of your Complaints Triage Model. They will ensure that next steps are the best steps for each case.

- Do not use mediation when an employee has suffered psychological injuries. If not, use only trauma-informed mediators.

- Have a list of trauma-informed investigators

- Normalize and reward bystander intervention. Show that your procedures are successful.

- Audit organizational structures and culture for patterns of institutional betrayal or systemic exclusion.

- Embed values-based leadership development and reflective supervision into performance review processes.

Closing Summary

Workplace bullying and mobbing are not personality conflicts or isolated incidents, they are systemic threats to human dignity, organizational integrity, and psychological safety. Understanding these behaviors’ scale, structure, and impact is critical for prevention, accountability, and repair.

The difference between bullying and mobbing is more than semantics. It reflects how deeply harm can spread when individuals, peers, and leaders engage in or tolerate abuse. Whether the behavior is top-down, bottom-up, or lateral, the damage is real for all forms of bullying, and the consequences are lasting.

Organizations must look hard and examine their culture, leadership, and values. Ending these cycles requires more than policies, it demands courage, education, structural reform, and a commitment to integrity at every level. The first step toward change is individual and collective accountability. Without it, we remain complicit.

No workplace is immune, but every workplace has the power and responsibility to prevent Psychological Safety Violators from causing harm. It starts with awareness and ends with action.

Linda Crockett MSW, BSW, RSW, SEP