Linda Crockett MSW, BSW, RSW, SEP, CPPA

In recent years, the term ‘trauma-informed’ has surged in popularity. It’s being used across social media, on professional bios, and in training program titles. However, this widespread use has led to dilution, misuse, and, in some cases, exploitation of the term. This not only undermines the credibility of genuine trauma-informed practices but also risks causing harm to individuals who may be misled by false claims. Many individuals are now labeling themselves as trauma-informed experts, but what does that truly mean? And how do we separate substance from superficial branding?

At its core, being trauma-informed means understanding how trauma impacts the brain, body, and behavior, and responding in ways that foster safety, trust, empowerment, and healing. It involves shifting from a mindset of ‘what’s wrong with you?’ to ‘what happened to you?’ and adjusting systems, policies, and interactions accordingly.

The rising popularity of trauma-informed language began gaining traction in mainstream discourse around 2018–2019, particularly in the education, healthcare, and HR sectors. However, the term existed long before that, rooted in research from the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study in the 1990s and the growing fields of neuroscience and trauma recovery. People often ignored me when I began using the term 15 years ago. Even among professionals, some genuinely asked, “What do you mean by that?” To this day, I still encounter licensed trauma therapists who ask me to explain what being trauma-informed entails. This lack of knowledge shows how loosely the term is understood and how critical it is to clarify its meaning.

Being trauma-informed is not just a trend. It’s not about buzzwords or hashtags. It is a profound, long-term commitment to understanding, addressing, and responding to the impact of trauma at every level of human interaction, individual, organizational, and systemic. It’s also essential to recognize that trauma-informed practices, whether you are an expert, practitioner, or supporter—will vary depending on the type of trauma you’re working with. For example, my area of specialization is workplace psychological hazards, such as harassment, bullying, mobbing, exclusion, and organizational betrayal. In these contexts, trauma-informed approaches require an understanding of power dynamics, chronic stress, reputational harm, and systemic dysfunction. Examples include adopting workplace investigations to avoid re-traumatization, ensuring employees feel safe when reporting harm, educating leadership on psychological safety, and addressing organizational silence or complicity. These practices will differ significantly from trauma-informed care in the context of domestic violence, child abuse, or medical trauma, which require their distinct framework and responses.

So, let’s break it down.

1. Deep, Evidence-Based Knowledge: A trauma-informed expert has a strong foundation in the science of trauma.

This includes:

- An understanding of trauma theory, neuroscience, and attachment theory.

- Awareness of PTSD, complex trauma (C-PTSD), developmental trauma, and intergenerational trauma.

- Familiarity with how trauma manifests in the body and brain (e.g., polyvagal theory, window of tolerance, somatic memory).

- Training in the intersection of trauma and systems of oppression (racism, classism, ableism, sexism).

This knowledge comes from in-depth study and experience, not Instagram reels or weekend certifications. It requires formal education, supervision, peer-reviewed research, and, often, years of hands-on experience.

As trauma-informed experts, we understand the importance of transparency in our qualifications. We know that taking a single course does not make someone an expert. Experts build their skills through in-depth training, ethical supervision, and substantial hands-on experience that spans years, not months. This transparency maintains trust, credibility, and ethical practice in our field.

2. Expertise is crafted through the crucible of real-world application and enriched by lived and professional experiences.

A trauma-informed expert has:

- Extensively worked with trauma survivors in clinical, coaching, social work, training programs, and organizational settings.

- Navigated complex power dynamics, resistance, disclosures, and systemic barriers.

- Experience what works and what doesn’t in practice, not just theory.

- In many cases, they are also trauma survivors who have done the personal healing work necessary to stay grounded and safe for others.

3. Integration Into Systems and Environments Being trauma-informed is not a one-on-one practice alone. It’s about systems change. Experts in this field:

- Embed trauma-informed principles (safety, choice, trustworthiness, collaboration, empowerment) into organizational policies and procedures.

- Train and mentor leadership and frontline workers to operationalize those values.

- Create accountability structures, not just awareness workshops.

- Ensure accessibility, inclusion, and culturally responsive care are built into the system.

It’s essential to customize trauma-informed systems’ integration according to the specific type of trauma being addressed. For example, within workplace environments dealing with psychological hazards like bullying, harassment, or mobbing, trauma-informed integration might involve rewriting investigation procedures to minimize harm, redesigning leadership evaluations to include psychological safety measures, or creating confidential pathways for reporting without fear of reprisal. By contrast, trauma-informed integration will look very different in healthcare or justice settings, focusing on patient care practices, informed consent protocols, or courtroom procedures. Context determines the method.

4. Ongoing Supervision, Reflection, and Accountability: Experts know they never stop learning.

They:

- Seek regular supervision or consultation.

- Own their limitations and refer out when necessary.

- Reflect on feedback and stay humble.

- Operate within clear ethical guidelines and professional standards (e.g., licensure, codes of conduct, DEI commitments).

5. Trauma-Informed Is More Than Kindness Yes, empathy matters. But being trauma-informed is not just about being “nice.” It’s about recognizing the profound impact of trauma on trust, perception, behavior, and learning. It’s about:

- Knowing that triggers aren’t always visible.

- Understanding that certain behaviors are survival responses (not bad behaviour).

- Creating brave spaces, not just safe spaces.

- Holding power with care and checking your own biases constantly.

Red Flags to Watch For

- Self-proclaimed experts with no credentials or lived/professional experience.

- People who center themselves more than survivors.

- Programs or trainers who avoid talking about systemic oppression.

- One-size-fits-all models that disregard culture, identity, and intersectionality.

- Claims of trauma-informed practice with no accountability, no policies, and no consequences for harm.

Trauma-Informed Practitioner: Applying Principles Without Claiming Expertise

A trauma-informed practitioner applies trauma-informed principles in their work without claiming to be an expert. Their role is crucial in creating safer systems, especially in leadership, HR, legal, healthcare, and investigative roles.

It’s important to remember that not everyone who integrates trauma-informed principles into their work needs to be a certified expert. Encouraging more people, especially leaders, HR professionals, lawyers, healthcare providers, and workplace investigators, to adopt trauma-informed practices is vital. Everyone’s contribution is valuable in creating safer systems, and we all have a crucial role in this critical work.

You can begin this journey by:

- Educating yourself through credible sources, books, and reputable training programs.

- Practicing trauma-informed values such as safety, trust, and empowerment in daily interactions.

- Listening deeply and responding without judgment.

- Respecting confidentiality, boundaries, and choice.

- Being mindful of power dynamics in your role.

Being trauma-informed as a non-expert means you understand that trauma can shape behavior and perception, and you adjust your approach accordingly. It’s also important to recognize that how these principles are applied will depend on the context of trauma. For example, a workplace investigator handling a psychological harassment case must know how re-traumatization can occur through power imbalances, poor communication, or procedural unfairness. A coach supporting a burned-out employee may need to understand the impacts of chronic stress and isolation. Practitioners working in justice, healthcare, or educational settings will have very different considerations, but all require the intentional application of trauma-informed values.

It’s not about being perfect. It’s about being aware, respectful, and willing to grow.

Trauma-Informed Supporter: Foundations Without Formal Practice

For those just beginning their journey, or those who don’t hold formal roles in trauma response but still want to contribute, there is an essential place for trauma-informed supporters. These individuals may not yet be trained practitioners or experts but are committed allies.

A trauma-informed supporter:

- Is trauma-aware and eager to learn.

- Seeks to understand the basics of trauma’s impact on others.

- Engages respectfully with colleagues or clients who may be struggling.

- Supports trauma-informed culture shifts by modeling patience, kindness, and inclusivity.

- Avoids giving advice beyond its scope and encourages people to seek qualified help.

These supporters often play a quiet but influential role in workplaces, communities, and families. The way they support others will also depend on the specific context. For instance, a team assistant noticing exclusion or microaggressions in meetings might speak up or check in privately. Volunteers supporting survivors may listen without judgment while guiding them to qualified help. A trauma-informed supporter in a school may recognize a student’s behavioral response as a trauma signal rather than a discipline issue. Support varies depending on the context, but it always involves showing care and respect and staying within limits.

Being a supporter is a steppingstone, it can grow into practice or expertise or remain a deeply valuable role.

The Bottom Line

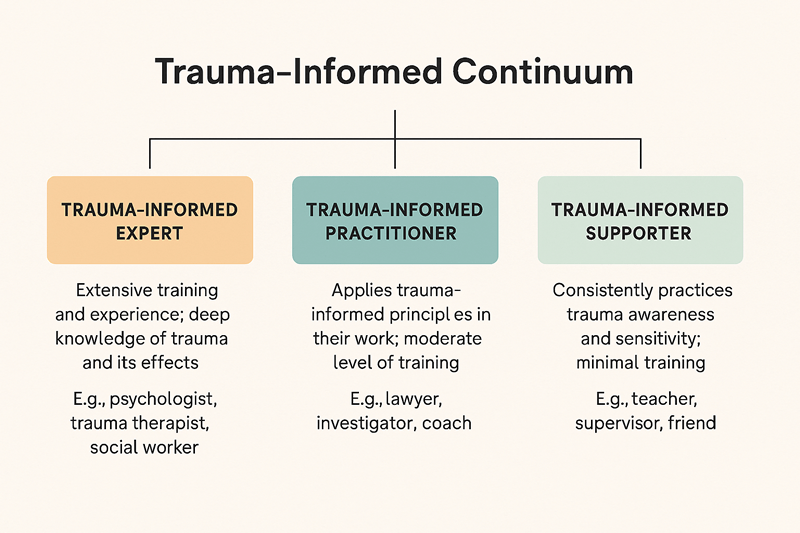

There is an essential distinction between a trauma-informed expert, a trauma-informed practitioner, and a supporter.

A trauma-informed expert has years of direct experience, advanced education, and ethical oversight. Examples include licensed trauma therapists, clinical social workers, trauma-informed organizational consultants, advanced trainers, and researchers. They lead training, develop policy, and guide complex cases.

A trauma-informed practitioner actively integrates trauma-informed principles into their day-to-day work with ongoing training and reflection but does not claim deep specialization. This category may include professionals such as lawyers, workplace investigators, coaches, HR managers, educators, and healthcare providers committed to trauma-informed engagement within the scope of their roles.

Trauma-informed supporters build awareness, choose respectful behaviors, and contribute to safer environments without practicing or advising beyond their knowledge. Examples include administrative staff, students, caregivers, volunteers, peer allies, or community members who are learning and striving to be more trauma-sensitive in showing up for others.

Each role has value and supports cultural change. What matters most is honesty about where you are and a commitment to keep growing.

If someone calls themselves trauma-informed, ask: What training have they done? What experience do they bring? Who supervises them? How do they demonstrate accountability?

Being trauma-informed is a way of being, not just a label. It shows up in how we listen, lead, and serve. It requires skill, humility, and a lifelong commitment to doing better.

It’s not a trend. It’s a responsibility, with room for everyone willing to do the work.

Being trauma-informed requires more than knowledge, it demands humility. The moment we think we’ve mastered it, we stop listening. True trauma-informed practice means showing up every day with curiosity, accountability, and a willingness to keep learning.

Linda Crockett

www.instituteofworkplacebullyingresources.ca

www.workplaceharassment.ca

psychologicalsafetyfirst@gmail.com